WAMCATS linked Fairbanks to the rest of the world

|

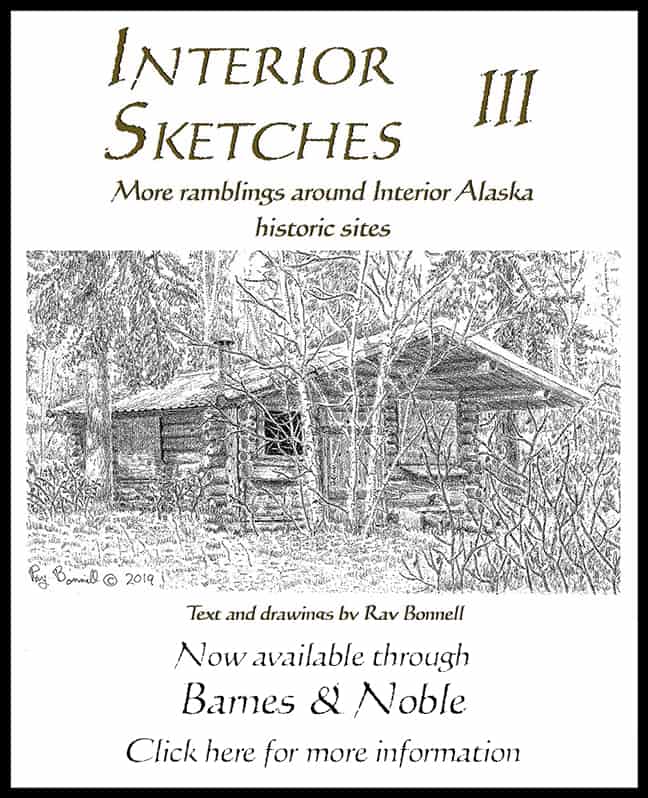

| McCarty telegraph station at Big Delta State Historical Park |

When I started reading early editions of Fairbanks newspapers certain things piqued my interest. For instance, some issues from the 1910s printed announcements for goods soon arriving from Valdez via the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail. How did Fairbanks businesses, isolated in Interior Alaska, know when something was coming?

Then I learned that running parallel to parts of the trail were telegraph lines—a segment of the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS). Cargo lists for stages could be telegraphed from Valdez, and travelers had access to the line at telegraph stations about 20-30 miles apart along the trail (often near roadhouses). Indeed, from its earliest days, Fairbanks, though physically isolated, was connected to the outside world by telegraph.

The U.S. government, spurred by the Klondike gold rush, had established Army posts across Alaska at the close of the 1890s, including Fort Davis at Nome, Fort St. Michael near the mouth of the Yukon River, Fort Gibbon at Tanana on the Middle Yukon, Fort Egbert at Eagle (six miles from Canadian border) and Fort Liscum at Valdez. In 1900 the U.S. Army Signal Corps began constructing a telegraph system to link those posts with each other and the contiguous United States.

Amazingly, the entire system was completed and operating within five years. A link with the rest of the world was actually established by 1901 when a line was run from Fort Egbert at Eagle to Dawson City in Canada. (Canadian authorities had already strung telegraph lines from Dawson City and Whitehorse to British Columbia.) The U.S. however, wanted an “All-American” system, so submarine cables were eventually laid from Valdez to Southeast Alaska and Seattle.

The system, as completed in 1904, included 1,439 miles of land lines, a 107-mile wireless link across Norton Sound, and 2,079 miles of submarine cable. Congress judiciously planned for civilian as well as military use of the new system and by 1906 about 80 percent of all messages sent across the government wires were civilian in nature.

A telegraph line to Fairbanks wasn’t included in the original plans. The telegraph line from Fort St. Michael would have followed the Yukon River most of the way to Eagle, but Felix Pedro’s 1902 gold discovery changed that. The line from St. Michael was diverted at Tanana and quickly extended along the Tanana River (with a slight detour to Fairbanks) to link up with the WAMCATS Eagle-Valdez section.

The telegraph station at McCarty (now called Big Delta and Rika’s Roadhouse) is shown in the drawing. McCarty Station originally consisted of at least four log structures containing the telegraph office, living quarters and warehouse space. Several of those buildings have been restored and are now part of Big Delta State Historical Park. The building pictured has been outfitted to reflect the life of the early telegraph operators.

WAMCATS landlines, because of harsh winters and poor soil conditions, were extremely hard to maintain, and as sections wore out they were replaced by less expensive, more dependable and more easily maintained wireless telegraph (radio) communications. All the telegraph stations that supported land-lines had closed by 1925 but McCarty received a 50 watt radio in 1926 which was in operation until 1935. That same year the WAMCATS buildings were transferred to the Alaska Road Commission (ARC).

With the switch from telegraph to radio, WAMCATS was renamed the Alaska Communications System (ACS), still under Army control. ACS wended it way from Army to Air Force control and eventually to private ownership. As a private corporation it was renamed Alascom and is now part of AT&T. (For a brief history of the system after it became ACS click here.)