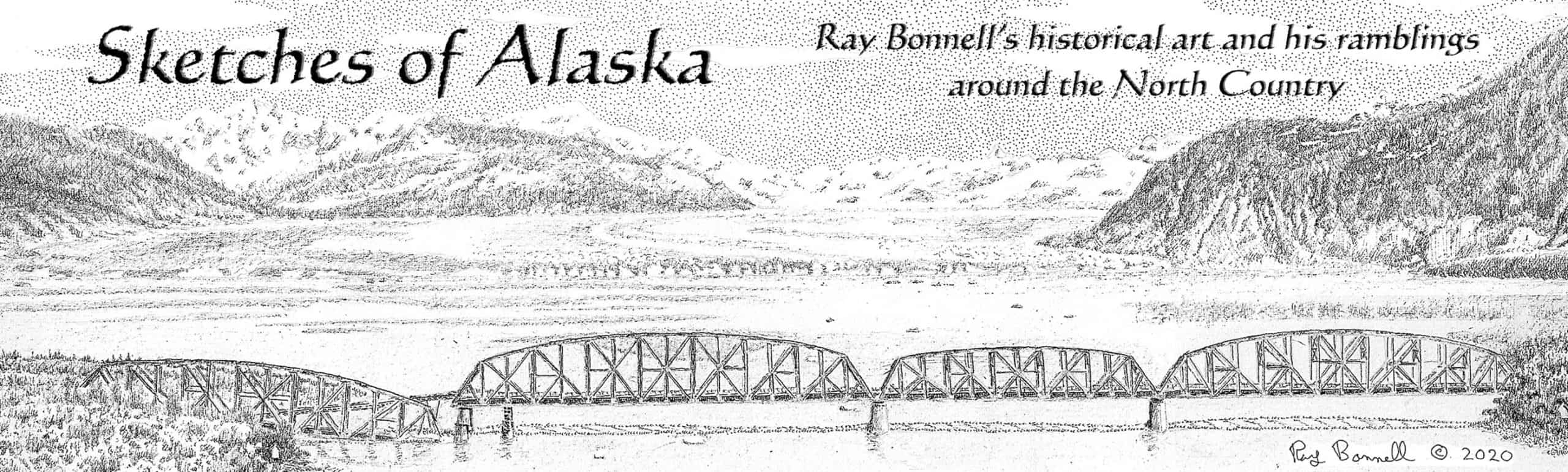

“Million Dollar Bridge” survives Copper River adversities and the 1964 earthquake

Million Dollar Bridge in the 1970s

Numerous routes were considered for a railway to the Kennecott copper mines in the Wrangell Mountains. The most direct route was along the Copper River, but engineers hired by the Alaska Syndicate (which controlled the claims) considered that route unfeasible.

Lone Janson, in her book “The Copper Spike,” said, “The Copper was everything that ornery rivers are noted for, and then some. Besides icebergs, rapids and shifting sandbars, there was the ‘Copper River wind,’ a force to be reckoned with as it coated everything in its path with sheaths of solid ice.”

A major problem area was the section of river where the Copper transitioned from delta to mountains. At the delta’s northern edge, two glaciers — Childs to the west and Miles to the east — faced each other across the river and conjoined Miles Lake. Only three miles separated the glaciers, and the termini of both glaciers calved icebergs into the river. Any railroad along the river would somehow have to circumnavigate the glaciers.

In addition, directly to the north was Baird Canyon, a steeply-walled gorge with meager evidence that a railbed could be built through it. Syndicate engineers felt that this chokepoint would doom any attempt to build a railway. But Michael Heney, builder of the White Pass and Yukon Route Railway, had read Lt. Henry Allen’s 1885 account of ascending the Copper River, and felt that the route might be feasible.

In 1904, Heney’s representatives personally investigated the route. Based on their favorable report, Heney obtained the right-of-way for a railway along the Copper River, including the only possible route past the glaciers and through Baird Canyon.

Heney and his backers had no intention of building a railway all the way to the mines — they simply wanted the Alaska Syndicate to buy them out when other routes, such as the Keystone Canyon route out of Valdez, proved unpracticable. Their ploy worked. The Syndicate purchased their interests in 1907.

A bridge crossing the river between Childs and Miles Glaciers was essential, and during 1907-1908 engineers studied the area. Some of their observations illustrate problems encountered in designing the bridge: water-level fluctuations of 24 feet, passing icebergs that jutted 20 feet out of the water, and wind speeds that occasionally exceeded 90 miles-per-hour.

Bridge work began in spring 1909 and proceeded throughout the next year. Contrary to some naysayers’ predictions, the bridge was not wrecked by the 1910 spring breakup, and it was completed by June of that year.

The bridge, which is officially named Miles Glacier Bridge, cost $1,424,775 to build — hence its unofficial name, the “Million-Dollar Bridge.” It is 1,550 feet long, and includes four steel through-trusses. The truss ends rest on concrete piers that are constructed on top of caissons sunk deep into the river bottom. From south to north, the trusses measure 400 feet, 300 feet, 450 feet and 400 feet.

The Copper River and Northwestern Railway was completed in 1911 and operated until 1938, when the mines closed. The Kennecott Corporation donated the railway r-o-w to the Territory of Alaska in 1941. The railway’s tracks were torn up during World War II and the Territory began converting the railbed and bridges for use by motor vehicles.

The 1964 Good Friday Earthquake caused extensive damage to the Miles Glacier Bridge, dropping one end of the northernmost truss into the river. The drawing depicts the bridge after a ramp was installed in 1973 to restore vehicular traffic. In 2004-2005 the dropped span was raised and other repairs made to the bridge. Unfortunately, another bridge downriver from the Miles Glacier Bridge washed out in 2012, severing the road connection with Cordova. At present the Miles Glacier Bridge can only be accessed by boat or plane.

Sources:

- “Glaciers Along Proposed Routes Extending The Copper River Highway, Alaska.” Roy L. Glass. U.S. Geological Survey. 1996

- “Million Dollar Bridge, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Christine A. Storey. National Park Service. 2000

- “The Copper Spike.” Lone E. Janson. Alaska Northwest Publishing. 1975