Life on the Line in Fairbanks historic red light district

|

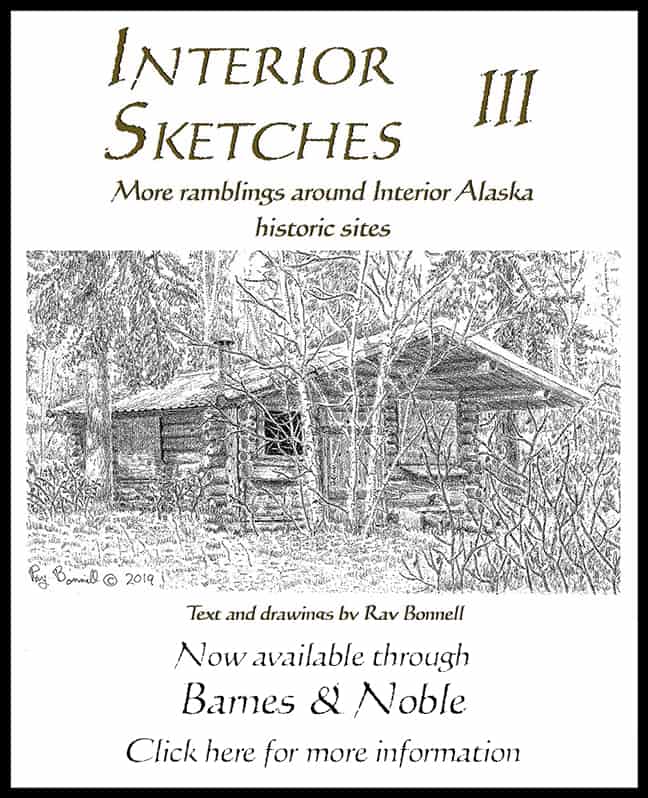

| Prostitute’s crib at Pioneer Park Gold Rush Town |

Economic depression gripped most of the western world during the 1890s, so not surprisingly, thousands of stampeders raced north during the 1897 Klondike gold rush. The majority were men, but (since depressions are equal opportunity oppressors) a goodly percentage of women chanced the trip as well.

All were lured by adventure and the possibility of riches—however women were disadvantaged in finding fortune. Mining was essentially closed to them because of social mores and the physical strength required. Consequently, women were usually relegated to domestic work. A significant number of northbound women were prostitutes and professional entertainers though.

About 80 percent of the population in the Yukon and Alaska was male. Prostitution was viewed as a “necessary evil”—required to satisfy the needs of the predominantly male population and protect “respectable” women from potential abuse. In communities across the region, governments decided the best way to control prostitution was segregating the ladies in “restricted districts.”

According to Lael Morgan’s book, Good Time Girls of the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush, Judge James Wickersham (who moved his court to Fairbanks in 1903) instituted a policy of “moderately taxing vice for civic betterment.” Prostitutes and others on society’s fringe, such as gamblers, were tolerated but required to pay monthly fines (essentially license fees) which helped support city government.

Because of this encouragement and lax law enforcement, by 1906 Fairbanks was a rough and tumble town. Episcopal Archdeacon Hudson Stuck was dismayed by the frequent violence (often instigated by pimps and their ladies) but believed outlawing prostitution was unrealistic. His suggestion to the city council was a separate district for prostitutes, similar to the one established at Dawson in 1899.

With city backing (if not official approval) the red light district, soon called the “Line” or “Row,” was established at the edge of downtown, between Cushman and Barnette Streets along Third and Fourth Avenues. Prostitutes had to confine their services to the district, with no solicitation allowed elsewhere. The district was regularly patrolled, and as long as the ladies paid their monthly “fines,” they had no fear of police harassment. The prostitutes also agreed to routine health screenings. Within a few years the city also passed ordinances minimizing the role of pimps.

In 1908 a fence with gates was erected across both ends of the district to protect the sensitivities of respectable people. Not that much occurred outside. Prostitutes’ more discreet activities were confined to their small cabins (called “cribs”). The 9’ x 12’ single-room log cabin in the drawing is one such crib. Now at Pioneer Park, it originally stood along Fourth Avenue. Cribs varied considerably. Some were multi-room frame structures. A few even had second stories with gable windows.

Most of the cribs actually faced inward—their living rooms with large picture windows and doors opening on to the alley between Third and Fourth Avenues. It was along the alley’s boardwalk that men would go “window shopping.” If a lady’s window shades were open then her trade goods were available.

There was little trouble along the Line for most of its existence. Some contemporary writers spoke of the Northern ladies as a breed apart from prostitutes elsewhere. Judge Wickersham wrote that they were “of a more robust class than usual among their kind… less addicted to criminal activities outside of those peculiar to their mode of life.”

The ladies of the Line were tolerated by respectable society (even if not allowed to actively mingle), and they were known to support local charities and grubstake prospectors. Patrons felt little fear that prostitutes would take more than their fair share of a miner’s poke, and some miners even left valuables with their favorite ladies for safekeeping.

The Line survived almost 50 years, but was finally closed in 1952, not because of local opposition, but at the insistence of the federal government. Most of the cribs were demolished in the mid-1950s, eventually replaced by Safeway and Woolworth stores.

Sources:

- Ghosts of the Gold Rush, a walking tour of Fairbanks. Terrence Cole. Tanana-Yukon Historical Society. 1977

- Good Time Girls of the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush. Lael Morgan. Epicenter Press. 1998

- Old Yukon: Tales—Trails—Trials. James Wickersham. Washington Law Book Company. 1938.

- Signage along Fourth Avenue. Fairbanks North Star Borough Historical Preservation Commission