A modern Alaska artist helps preserve Chitina history

|

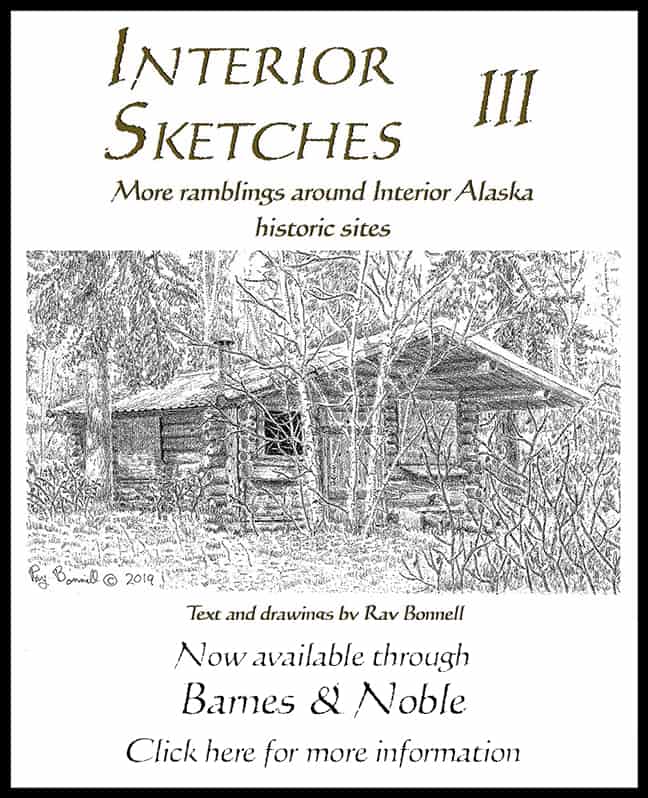

| Spirit Mountain Artworks (old tin shop) in the 1990s |

Emil Goulet moved to Alaska in 1931 looking for work. He stopped in Chitina on his travels, and in his book, Rugged Years on the Alaska Frontier, wrote of taking “an immediate liking to the little village which nestles in a deep valley. … The mountainsides were covered with spruce and birch. In the center of town was a small, almost round lake. … In addition to the drug store and post office, there was a general store, clothing store, depot and roundhouse, two hotels, federal jail, a small one-room school house, government road commission buildings, and a few scattered small homes.” He wrote later that Chitina also boasted electricity and a water system.

The builders of the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad (CR&NW) established Chitina in 1910 as a junction on the way to the copper mines up the Chitina River. The Valdez-Fairbanks Trail (also called the Richardson Trail) was only 40 miles to the northwest, and developers had visions of those Chitina River tracks being only a branch line, with the main line running from Chitina up the Copper River Valley and on to the Yukon River.

Indeed, according to Lone Janson’s book, The Copper Spike, an Alaska Railroad Commission appointed by President Taft recommended extension of the CR&NW Railroad from Chitina to Fairbanks as a better choice than the alternative Seward-to-Fairbanks route. Political considerations, however, meant that the dreamed-of extension never materialized.

So Chitina made-do with the “Edgerton Cut-off,” a road extension connecting Chitina with the Richardson. The Edgerton was completed by the time the CR&NW reached Chitina in 1910, and most passenger and freight traffic headed out of Valdez for the Copper River Basin and Fairbanks began bypassing the section of the Richardson over Thompson Pass. Stage lines that had run between Fairbanks and Valdez quickly dropped Valdez from their route, shifting to Chitina as their southern terminus.

Chitina quickly became the commercial and governmental center of the Copper River Valley. The Alaska Road Commission (ARC) even made the town its district headquarters.

The town’s glory days lasted until 1938, when the Kennicott mines closed and the CR&NW ceased operations. Chitina didn’t become a ghost town overnight, though. According to U.S. Census reports, the town’s population in 1930 was 116. In 1940, two years after the railroad’s demise, it was 176. By 1950, Chitina’s population had declined to 92, and by 1960 only 31 people resided there.

One of the first permanent buildings in Chitina was Fred Shaupp’s tin shop. Fred came to Alaska during the gold rush period, first setting up shop in Nome, then Fairbanks and then Chitina. According to National Register of Historic Places documents, he erected the tall, narrow wood-frame building over his tent in 1910.

The original shop was a two-story structure, 17 feet by 33 feet, with 12-foot ceilings on the first floor (Fred evidently needed plenty of work space) and rough wood siding. About the time the railroad was abandoned, a 15-foot two-story extension was added at the rear. A new basement was dug utilizing rails salvaged from the railroad as footings for the foundation, and the entire building was re-sheathed with milled siding pulled from derelict railroad buildings.

Over the years, the tin shop itself became a derelict and was in danger of collapsing until artist Art Koeninger rescued it in 1978. Koeninger purchased the building with thoughts of salvaging some of the lumber to build a cabin. He quickly decided to restore it instead.

With grants from the State of Alaska, Art and a crew of volunteers rebuilt the structure. Their first job was putting in a new foundation (Art told me that it was quite a feat extracting the old rails buried underneath the building). They restored the exterior to its original appearance, but gutted the interior, essentially building a modern, energy-efficient structure inside the old shell. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979

The building’s first floor now houses an art gallery, Spirit Mountain Artworks (named for a prominent peak south of town), and Koeninger’s workshop, with a residence on the second floor. It is one of only three original buildings left on Main Street in Chitina.

Sources:

- Art Koeninger interview with Bill Schneider and Dave Krupa. University of Alaska Oral History Collection. 10-22-1993

- Conversation with Art Koeninger, current building owner of building. 2015

- “Real Art Thrives in the Shadow of Spirit Mountain.” Mike Dunham. in Anchorage Daily News. 5-32-1996

- Rugged Years on the Alaska Frontier. Emil Oliver Goulet. Dorrance & Company. 1949

- The Copper Spike. Lone E. Janson. Alaska Northwest Publishing. 1975

- U.S. Census reports for 1930, 1940, 1950 & 1960