Parts of the Valdez-Eagle Trail can still be walked

|

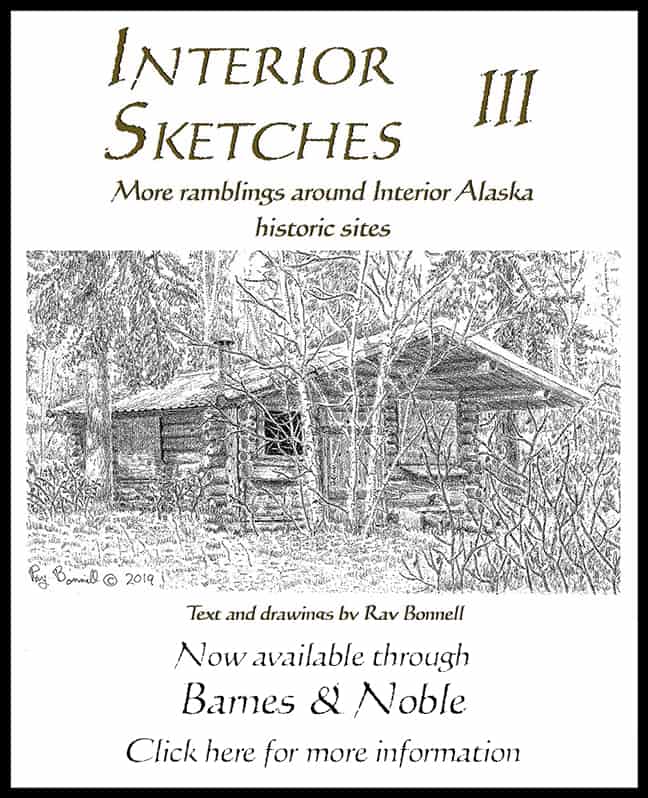

| Segment of Valdez-Eagle Trail at Eagle Trail State Recreation Site in Fall 2016 |

In the wake of the first wave of stampeders to the Klondike Gold Rush, U.S. Army Captain P.H. Ray was sent to Alaska in 1897 to investigate rumors of unrest among gold-seekers along the U.S. portion of the Yukon River. During his travels, Ray heard from prospectors clamoring for an “All-American” route to the Yukon gold fields that would bypass the Canadian-controlled White Pass and Chilkoot Trails.

Ray recommended that a military trail be built from the ice-free port of Valdez on Prince William Sound to the Yukon River Basin. In the summer of 1898 U.S. Army Captain William Abercrombie came to Alaska to reconnoiter routes for the trail.

Abercrombie discovered horrendous conditions at Valdez. Unscrupulous promoters had convinced 4,000+ Yukon gold-seekers to attempt a trail out of Valdez. However, the trail they promoted took travelers across the Valdez and Klutina glaciers and down the tumultuous Klutina River.

Ken Marsh, in his book, The Trail, the story of the historic Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, estimates that only a quarter of those who attempted the Valdez Glacier trail made it as far as the Copper River, and only a handful pressed on to the Klondike. Numerous gold-seekers lost their lives on the treacherous glacier crossing, and Abercrombie estimated that 95% of those who survived the glacier trek wrecked their boats descending the Klutina River. Of those who gave up and returned to Valdez, most ended up destitute.

Captain Abercrombie returned to Washington, D.C. later that year to present his report. In 1899 he traveled back to Valdez to begin construction of a “Trans-Alaska Military Road” from Valdez to Eagle (via a glacier-free route). Abercrombie hired many of the destitute argonauts as construction workers.

Workers built 93 miles of packhorse trail, and blazed another 112 miles of foot trail that year. The military road, also referred to as the Valdez-Eagle Trail, was completed by 1901.

Following Native trails for much of its length, the 425-mile-long trail crossed the Chugach Mountains, then followed the Copper River north and northeast before crossing the Mentasta Mountains. Coming out of the mountains near the Tanana River, the trail swung northwest, crossing the Tanana near present-day Tanacross and going on to the Athabascan village at Lake Mansfield. Thence it climbed northeast through another Athabascan village called Ketchunstuck into the Fortymile River region before tacking to the east through the gold camp of Franklin and then north to Eagle.

The Trans-Alaska Military Road was never more than a packhorse trail, and its years of service were few. By the time the trail was completed the Klondike Gold Rush was winding down.

Then, the discovery of gold in the Tanana Valley diverted attention away from Eagle. Starting in about 1903 gold-seekers began peeling off from the Valdez-Eagle Trail at Gakona, headed for Fairbanks. The lower half of the trail became part of the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, while travel along the northern half declined.

During the trail’s early years, the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS) constructed telegraph lines between Valdez and Eagle, with telegraph stations located approximately every 40 miles. A Bureau of Land Management brochure states that soldiers operating and maintaining the telegraph system frequently used the trail, but even that usage began disappearing in 1909 as WAMCATS gradually converted to wireless telegraphy.

There was active mining in the Fortymile region so the trail between there and Eagle remained well-traveled. However, subsistence activities and other localized travel became predominant along most of the Valdez-Eagle Trail north of Gakona. It would take later mineral development and transportation needs to resurrect other portions of the trail.

The section of trail shown in the drawing, located 16 miles south of Tok at Eagle Trail State Recreation Site, is one of the few easily accessible segments of the original trail. Winding along the base of the mountains, it is now part of a short nature trail through the recreation site.

Sources:

- “History of the Valdez Trail.” Geoffrey Bleakley. Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve website. No date

- “The Eagle-Valdez Trail, Northern Portion.” U.S. Bureau of Land Management. No date

- The Trail: the story of the historic Valdez-Fairbanks Trail that opened Alaska’s vast Interior. Kenneth Marsh. Trapper Creek Museum. 2008

- Signage at Eagle Trail State Recreation Site.